On Feb. 13 Zhiyuan Robotics unveiled the full‑size humanoid YuanZheng A3 in a short video that traded the usual corporate polish for a show of physicality: the robot chained together flying kicks, aerial steps and a low‑sweeping whirlwind move in quick succession. The demonstration signals a pivot in Chinese humanoid robotics from single‑move demos toward continuous, multimodal motion that firms hope will translate into real‑world service tasks.

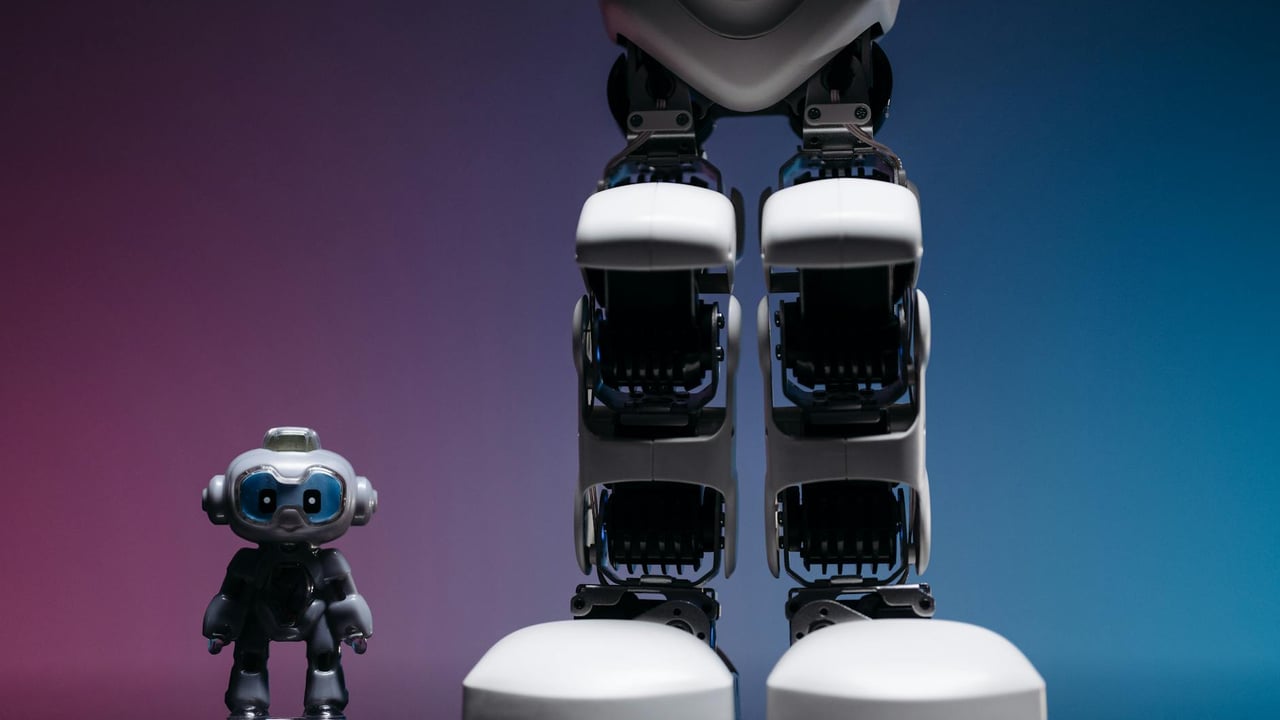

Engineering changes underpin the stunt work. Zhiyuan says the A3 has “super‑human” full‑body degrees of freedom, an arm endpoint payload of 3 kg and peak limb speeds of up to 2 m/s; a one‑to‑one flexible waist and an exoskeletal, lightweight leg design improve dynamic stability and expand joint range for extreme maneuvers. The company has also modularised its dexterous hand technology and redeployed it as an independent business unit, in part to accelerate commercialisation of manipulation capability.

Battery and interaction upgrades are aimed at turning spectacle into sustained service. The A3 uses an embedded dual‑battery trunk architecture that Zhiyuan says yields up to eight hours of mixed‑use operation with fast swap and rapid‑charge options, while a new multimodal interaction stack supports end‑to‑end proactive conversation, touch wake‑up and open developer interfaces. Those features are pitched at high‑frequency human‑robot contact points such as exhibition stands, reception desks and retail booths where continuous uptime and natural interaction matter.

The A3’s release has an unmistakable competitive edge: its choreography resembles public breakthroughs by rival YushU, which popularised acrobatic humanoid moves. Zhiyuan’s marketing emphasis on “how much it can do physically” reads as a challenge in a domestic contest over body‑level performance. Executives have pushed hard on hardware, components and intellectual property, while using capital to close supply‑chain gaps.

Beyond metal and motors, Zhiyuan is investing heavily in what the industry calls embodied intelligence — the data that teaches robots how to act in messy, real environments. The company established a large‑scale data capture center in Shanghai that covers more than 200 scenarios and reportedly produces tens of thousands of real‑machine and simulated samples daily, yielding a million‑plus real‑robot dataset. Zhiyuan’s spinoff Mifeng (觅蜂科技) now offers a full‑stack data service meant to overcome the sector’s shortfall of high‑quality training hours.

These twin tracks — improving the physical “body” and assembling the data “brain” — reflect a broader shift in the Chinese robotics ecosystem. Zhiyuan has also mobilised external capital, including a partnership with Hillhouse Capital to create an industry fund, and it has backed component and software suppliers to speed an industrial ecosystem around its platform. That vertical consolidation mirrors moves elsewhere in the robotics and AI industries, where control of hardware, parts and datasets confers a durable advantage.

Whether the A3 will move from showpiece to workhorse depends on durability, safety and economic fit. High‑speed acrobatics make for viral video, but service deployments demand predictable reliability, robust safety systems, and cost‑effective maintenance. The eight‑hour endurance and modular design help the commercial case, yet operators will judge the robot by its uptime in real shifts, integration costs and the subtleties of human interaction in crowded public spaces.

For an industry impatient to demonstrate utility, Zhiyuan’s A3 is proof that embodied capabilities are accelerating. The robot’s release will intensify competition over both hardware performance and the scarce, high‑quality datasets needed to train generalisable embodied models. Regulators, customers and investors should watch whether the next phase of demonstrations focuses on repeated, safe service runs rather than one‑off acrobatics.